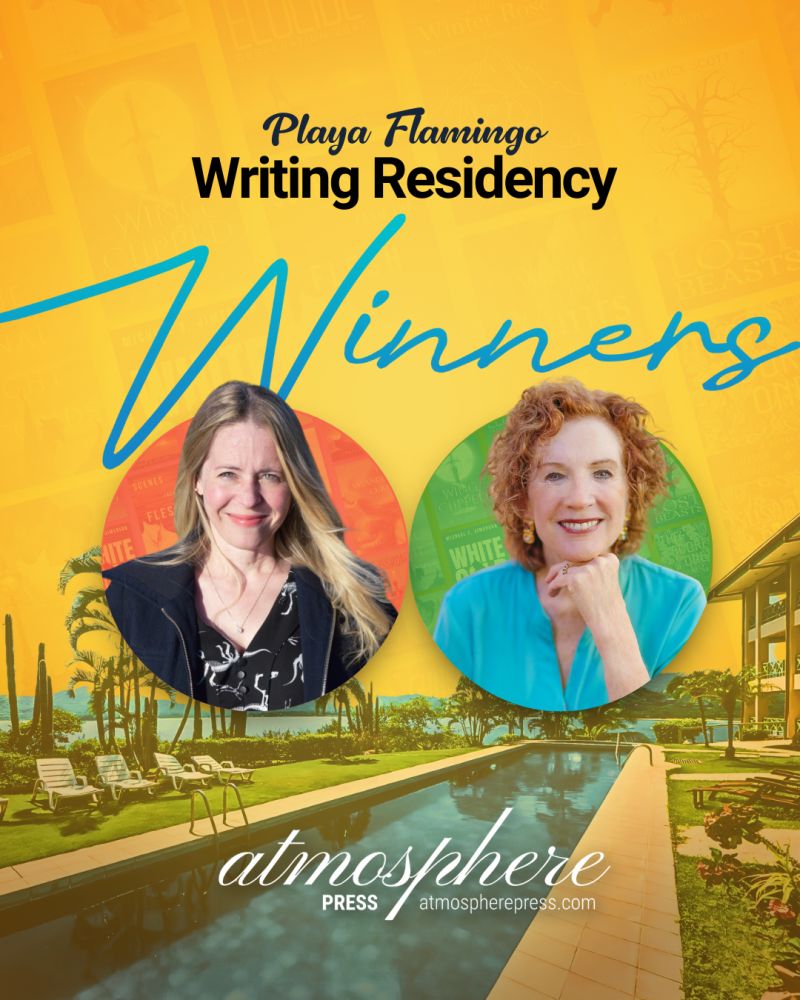

Joy Lanzendorfer is the author of the novel RIGHT BACK WHERE WE STARTED FROM. Other work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Atlantic, NPR, The Washington Post, Alta, Raritan, Ploughshares, The Guardian, Smithsonian, Alaska Quarterly Review, and The Poetry Foundation. Her nonfiction was listed as notable in The Best American Essays 2019, 2020, and 2022 and her article on the California condor was a finalist in the 64th Southern California Journalism Awards. The short story “Sleep Disturbance,” originally published in Forge Literary Magazine, was included in The Best Small Fictions 2019.

She has received grants from the de Groot Foundation and the Speculative Literature Foundation, as well as a Discovered Award for Emerging Literary Artists, funded by the Community Foundation Sonoma County and National Endowment for the Arts. She holds an MA from San Francisco State University and has been awarded fellowships and residencies from Wildacres Residency Program, Cuttyhunk Island Writers’ Residency, and Hypatia-in-the-Woods.

Joy lives near San Francisco with her husband and son. An avid nature lover, she became a certified Master Gardener in 2022. She’s also the host of What’s The Story?, a book-related radio show/podcast that airs every week on 95.9 FM The Krsh.

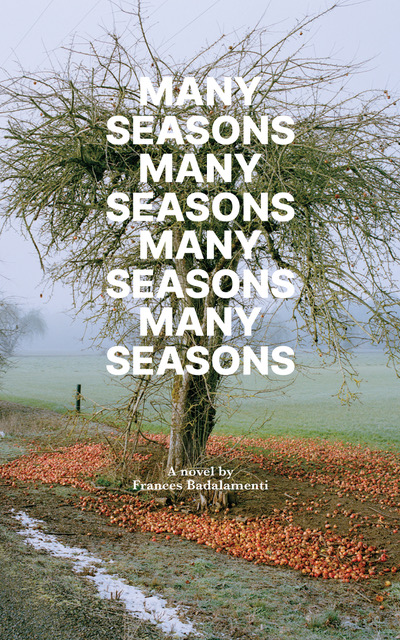

Right Back Where We Started From

Joy Lanzendorfer

Blackstone Publishing

What happens when you show up late to the Gold Rush?